bás in éirinn

on the search for home in Irish music and the spectre of death behind its shoulder: "dead towns" and "dying cities"; what's next for RÓIS and For Those I Love and my favourite Irish album of the year so far, Ithaca by Lullahush

A few months back I wrote a piece that used a disastrous early Fontaines DC interview as a launchpad for a discussion about just a handful of the thousand ways that Irish music can and should sound Irish, and in my last gig roundup I tried my best to figure out what exactly is Dublin-y in Dublin hip-hop, so matters of national identity have always been somewhat visible in Fourth Best's DNA, and in the music that is covered here. So much great Irish art exists in the form of dreams of home from foreign shores, or in the form of an artist reckoning with Ireland becoming home.

arriving there is what you’re destined for

Yearning with the best of them is Athens-based Lullahush, wearing that emotion on his sleeve by calling his new project Ithaca – for the homeland to which Odysseus strives to return in Homer's epic. In the press release for the project, he expands further on that title:

"My search for a sense of home since leaving has made me think about what Ithaca means. Maybe it's not a place, maybe it's a series of circumstances, maybe it's something internal, maybe it’s something you carry around with you."

a small thing but I love that the version of "come to Brazil!" in this video's comment section is "COME TO BIRR!"

Ithaca is first and foremost a trad album, a collection of reinterpretations of folk songs and iconic Irish tunes; and there are brief moments of near-silence on the record where that's all it is. However, the album coming from a label perhaps better known for releases by the likes of Flume and SOPHIE is a signpost of the road to come, as the album is otherwise an unending cascade of sound - the album opens with a warped birdsong and switched-on sean-nós, but chaos begins to roll out from the depths; the second track has a driving rhythm section of rumbling bass and percussion halfway between a bodhrán and a drum machine barrelling ever-forward against a collage of clips from sessions and stories far away; at one point a voice calls out "I miss the boys" and I never noticed until reading Eoin Murray's review that it's a clip from Lisa O'Neill's Rock The Machine. It gets only more abstract and psychedelic from there; the third track begins with glitched instrumentation tracing the chaotic fragments of Molly Bloom's ecstatic monologue at the end of Ulysees, before crashing into the yearning once more:

These twelve months and better my darling has left the shore

He ne'er will come back till he travels the globe all over

And when he returns with laurels I'll crown him all over

He's the fondest of lovers, sweet Jimmy mó mhíle stór

Then once more into the chaos, everything all at once, as though caught in the static while tuning between scenes from a life. I played the album for my partner who grew up between Dublin and Connemara and it's around this point in the record she invoked the name of The Caretaker, Leyland Kirby's hauntological project who once explored the progression of dementia on Everywhere At The End Of Time, a project where degrading tape loops come apart as fading memories slowly over the course of hours; Lullahush seems also to be focused on how memories warp and transform, life turning into vapour. The album cover, piles of seaweed forming complex layers and knots, is a shockingly tactile image. You can feel it. You can almost smell it.

The album twists further and deeper; monologues and poetry and family WhatsApp notes. The album's climax on Máire na Réiltíní has hundreds of beats per minute rushing kick drums bringing looming dread, before the clouds clear to sing Raglan Road with our loved ones once more. Like RÓIS before him he visits the handful of remaining recordings of keening, summoning Cití Ní Ghallchóir's voice from the tape to carry a melody that once risked being lost entirely.

I have been listening to barely anything other than Ithaca since I saw Lullahush perform live - opening for RÓIS. In that context the album comes with yet another surprise - as the body of trad tunes became the source text for Ithaca's mutations, on stage the album is performed mostly instrumentally with musicians with a traditional background. The sample collage and synth elements are still there, but seeing the emotional climax of Máire's drum-rush done on a kit rather than a drum machine alone would have you calling it one of the best gigs of the year. On Instagram ahead of the live show's first outing in Greece, Lullahush wrote:

We have been working on a set that emphasises risk, chaos and vulnerability to try find a living, breathing way to play this music. A reimagining of Ithaca rather than a recreation and very much an experiment.

Although I followed the rest of the Irish press in going ride-or-die for RÓIS, that show was my first time seeing her live. Her set is equally powerful; her voice is absolutely unmatched anywhere in Irish music and the MO LÉAN material changes shape somewhat in the room - Cití's voice a ghost in the machine, RÓIS' voice channelling it into the overcrowded Workman's space.

(forgive the tangent but it's not my favourite venue - I swear I've been to much more comfortable "sold out" shows there and it's not me getting old, but the crowds that night were too thick to get any photos in at all, the sound wasn't up to scratch and some gig-goers feeling the need to offer live commentary was a bit much. "her voice is insane" yes bro we're in the room with you. that's why there aren't many photos from this gig).RÓIS performs two sets. One dressed in black is more solemn and mournful; there the music is more clearly established in the world of keening. One dressed in red is everything else; the spectre of death still looms but rather than the immense sorrow of burial itself we see the confused high spirits of a wake; notes of jazz keys playing, infectious dance music, hip-hop (a sequence about somebody getting the ride at a wake-house features the phrase "to the wake house, for a riiiide" in Lil Jon window/wall cadence). Describing the Irish Wake Tour where both sets were performed, RÓIS noted:

One of the most fascinating aspects of the wake was its role in matchmaking. It was a place where the impermanence of life was most palpable. The wake was not just about mourning; it was also about embracing life’s most primal elements—sex, love, and death.

In Fourth Best's first proper outing on TikTok, I tried out the video essay format and covered some thoughts that listening to these records had stirred up in me, as well as an unlikely extra source of inspiration: Sinners, an action-horror movie by Ryan Coogler with music from Ludwig Göransson.

There are two scenes that I think everyone talks about when they talk about this film. One of them is an incredibly powerful sequence weaving the blues into a rich history of indigenous African music and snapping suddenly through time to R&B, hip-hop, even New Orleans Bounce music; the other is a choir of the undead performing of The Rocky Road to Dublin blown up to IMAX scale. The film is about trying to preserve music's ability to help us heal and to grieve at all costs, mourning the loss of our customs at the hands of colonialism and segregation.

When I think of Sinners though, the contemporary artist that most comes to mind is RÓÍS, who on her 2024 record MO LÉAN re-imagines keening, an old Irish tradition of funeral singing, for a modern age.

[...] There's only low single-digit number recordings of keening out there; one of Cití Ní Gallchoir in Donegal was taken by the American folklorist Alan Lomax in 1951 and forms the backbone of RÓIS's work; seeing her live and hearing her singing against that recording was one of my favourite moments at any Irish show in years. I often hear from Irish people that they find it strange to see how other English-speaking countries handle death; often waiting weeks for funerals and the likes; in that sense RÓIS's music is cathartic.

Years before Alan Lomax arrived in Ireland to record Cití, he wrote in The New York Times: “Our big problem is to realize man’s dream for democratic and peaceful plenty. Folklore can show us that this dream is age-old and common to all mankind. It asks that we recognize the cultural rights of weaker peoples in sharing this dream, and it can make their adjustment to a world society an easier and more creative process. The stuff of folklore—the orally transmitted wisdom, art and music of the people—can provide ten thousand bridges across which men of all nations may stride to say, "You are my brother."”

The TikTok came to a conclusion that I ended up sticking on a wall somewhere in Dublin City Centre:

Fourth Best has always been something that exists in opposition; most notably to things like streaming and AI in music. Lately it's been hard to focus on the music when an overtly far-right movement is seemingly winning in Ireland. A few weeks back, I attended a counter-protest against an anti-immigration march on Dublin powered by far-right parties and and backed by explicitly fascist organisations. While I'm proud of my comrades, we were terrifyingly outnumbered on the day. And now they're at my doorstep. Around the corner from where I live in Dublin 8 there's a "D8 Says No" camp that has been around for almost a month at this point; setting themselves up outside a school (and likely triggering an assault on the school premises) and claiming to be protesting the construction of an IPAS centre that appears to have been ruled out long ago, and rambling about developments that have gone by unnoticed for years. Lately they've been harassing a local pub for sticking to their antifascist principles and barring one of the pricks. When I rejoined TikTok to try and get Fourth Best moving on it, I found the amount of them in comment sections nauseating (and they're not in my comment sections either so I can't farm engagement off them.)

In trying to think what the best stories we have to take to that fight, I'm not only hopeful that we can make the case that we have the music, but I'm very thankful for the examples we have. In that TikTok I made, I used the case for one of the best Irish albums of last year showing the way forward:

In 2011, fleeing war and tragic loss, Mohammad Syfkhan landed in Ireland, found a community of musicians to work with throughout the years. He opened for Lankum at the Cork Opera House in 2023, and last year he released his brilliant album I Am Kurdish, recorded with musicians from Leitrim, and said this when the album was released:

"I especially thank the Irish people who have engaged with my music in such a wonderful way. I consider myself lucky to have come to this wonderful country that has welcomed me and all refugees. I thank God for everything, and now, thanks to this wonderful country, I am a musician and have a safe home. Thank you to the Irish government and people for giving me the honour of calling this country my home."

I don't know if we're doing right by him today, both government and people; shoving migrants into hastily assembled accommodations for the benefits of cowboy landlords or leaving them out in tents in the winter, watching so-called patriots set buildings ablaze rather than see them house a foreigner. I'm not foolish enough to think that music has the answer to that. But it has a role to play.

When writing that mini-script, I dropped out to DDR Alternating Current to get some footage of Mohammad Syfkhan performing. Before he took the stage, a speaker implored us to check out the Aparthied-Free Zones initiative for showing solidarity with Palestine.

Mohammad Syfkhan just implored us to dance.

not the set I attended, but I'll never miss a chance to show someone BYOL's beautifully-shot mid-day gigs, and this one is where you'll get maybe the best sense of what it's like to see one of those solo Syfkhan shows where he's crucially just up for the craic.

no one shouted stop!

As well as the songs from the wake-house, RÓIS has also mentioned a new set of material called Keening of a Dead Town - which should feature in some upcoming performances, and might be the basis for a new album. The work, written with Harry Hennessy, appears to be something of an adaptation of Death of an Irish Town (or No One Shouted Stop!), a book collecting writing of John Healy on the decline of Charlestown, Co. Mayo. I haven't been able to get my hands on a copy yet. It leaves behind a trail of endless citations - noted scenes depicting emigrants waving goodbye from the trains out of the town seem burned into the consciousnesses of some Irish writers, and the stories have been a tool for anyone to tell any story they like about Irish rural life. His name has shown up in some bizarre places - I saw someone cite both Healy and Karl Marx to rather ineffectively argue against... outdoor dining?

I feel comfortable in offering that we all know a town that is close to death; an eternal departing youth that sees no future there.

In a recent Glamour UK feature to promote her forthcoming album Euro-Country, CMAT seems to be circling around the same questions I am:

Surrounding her was this Irish culture boom: from Guinness to Paul Mescal’s every move, London and the wider world had the Irish on the brain. It made her confront her own complicated relationship to her identity. “I didn’t relate to any of it,” she says incredulously, curling her lip to bear her gem-studded teeth with a grimace. “Like, why am I seeing Claddagh rings everywhere? The GAA [Gaelic Athletic Association] jerseys? Why is everyone pretending we had this exact same childhood? There’s this very romantic vision of Ireland, but I grew up in a place where it’s not very fun to grow up. This fake version of our [Irish] identity was being built up by Americans and English people and claimed for themselves. So this album had to come out – to try to capture that for myself again.”

[...]

“A big problem that keeps rearing its ugly head is the lack of community – the lack of talking to each other, forming connections,” she explains. We’re a lone country, a state of commerce and capitalism, and that’s not easy to come back from – a ‘Euro’-led country. We have this culture of individualism and not caring for each other. That’s so much the reason for the rise of fascism.”

The town where I grew up at one point went on a PR blitz erected signs seemingly everywhere on the road going in, loudly exclaiming THIS IS A GREAT TOWN in bold all-caps serif. There were further signs listing the reasons why - "best playground in West Cork", "artisanal food suppliers", "inclusive society", "state of the art swimming pool" and so on. It's hard to explain why a local act of civic pride bristled so heavily against me. The main roads and all the investments bend around to the coasts, to serve Wild Atlantic Way tourists - so if you were inland enough to see them in the first place you probably already had a good sense of what kind of town the Town was already.

It felt like empty affirmation; the frog in the pot on the stove saying "this is a great temperature". So often I felt isolated and alone there - at no point in my life did staying feel realistic. When my brother returned there during the early days of the pandemic, I stayed and paid my Dublin rent. At least Dublin offered some chance of seeing my friends, even in the depths of the isolation days. Yet I often wonder if I did it to myself, that it was a GREAT TOWN all along, and that maybe my discomfort with it all is a trace of that same individualism that CMAT calls out.

I have to face my discomfort and figure out what it means to me.

Many many people took what CMAT had to say quite badly, removing it from its context in the process. "God forbid we try to reclaim our culture" Blue Niall said – breezing past the bit where CMAT said she made Euro-Country in part to try and recapture her Irish identity. "If you are struggling to connect with symbols of Irish heritage, I would encourage you to go deeper and ask why", in response to CMAT going deeper and asking why in public. CMAT and Blue Niall already agreed with each other. Everything ever published about Euro-Country points to it being an album that takes aim at the same forces Blue Niall has centred his mission around. For him, his music is an explicit attack on cultural imperialism.

CMAT's Euro-Country singles so far have been set in the universe of the Celtic Tiger; glamour models in stock photos selling god-knows-what, sexualised Euro coins and random mascots and being trapped in the corner of a nightclub with the KPMG suits. It skewers the hollowed-out culture that the Celtic Tiger made.

Kelly Earley's blog post How Ruining The Economy Made Us All Irish Again attempts to track the current surge in desire for an all-Irish identity and places a theory that it began at first with that hollowing - where climbing the class ladder once came with proximity to American goods; yearly shopping trips to NYC and Abercrombie & Fitch hoodies became a class marker, and the values of our society and education system as a whole were centred upon building people who are ready to serve the multinationals. A good job above all else. And you don't get a good job in a dead town. Earley's hypothesis on why we're so obsessed with Irishness is grim. I don't fully know if I subscribe to it. But it weighs on me:

The Irish Celtic Tiger aspiration was to live bigger and better. Now, the loftiest height to which Irish people will dare to aspire, is being able to afford to live in Ireland.

The Cork-raised, Dublin-based artist Brownsauce replied to Blue Niall's post with I think the central question of this section:

"If we’re going to keep mining Irish culture for aesthetics, we should at least be asking ourselves: what are we actually trying to say?"

"Whether it’s triskeles, Claddaghs, or Aran-knit patterns, there’s a wave of vapid self-expression that uses these icons as hollow signifiers of Irishness. They stand for nothing beyond a vague aesthetic — Irishness as branding.

And I’m not speaking from the outside. I’ve done it too. [...] Eventually, I realised that so much of what we were putting out on Instagram had been boiled down to basic visual signifiers — essentially just adverts. Find one familiar image — say, Mr. Tayto — then combine it with another “edgy” one — maybe an ecstasy pill. Photoshop them together, call it a design, screen print it, sell it.

Get likes print money. Repeat. Call content art and call it a day — made for consumption, Irishness stripped of context, and lacking any critical thought.

So I’m not coming at anyone in particular for making this stuff. I don’t think there’s anything inherently wrong with it. But I do think people are starting to cop on to the fact that a lot of what's being made right now feels like a gimmick.

It’s surface-level. Safe. Marketable."

Dr. Shubhangi Karmakar, who I first encountered selling jewellery and accessories to raise funds for the Coalition to Repeal the 8th Amendment, has called out Irish brands re-selling DHGate and drop-shipped tat as Irish jewellery, these brands frequently using Gaeilge and the image of Irish-owned/women-owned businesses while not being upfront about charging 10x the price of products from the wholesale websites.

I feel like I don't need to explain why I'm including this detail here, right? Why I think if we're serious about this "Revival" as some will call it, we shouldn't shut down criticism of the fact it's being used as a growth hack. As a hashtag. As another arm of the system that the "Revival" should go against. I also hate calling it a Revival. Independent Irish culture that speaks to Irish cultural history has always been here.

I love what the likes of Pellador are doing and the revived interest in Celtic traditional design in modern Irish fashion. Pellador are honest about what they're doing, they're making high-quality products and crucially they aren't resting on their laurels. I really like what they've done with the Fidchell jumpers, something that actually made me stop and research and learn something about our history while also looking excellent.

Now I'm writing from Barcelona, in the run-up once more to Primavera Sound. At one of the free city gigs on Monday I found a Catalonian band making odd sean-nós electro-pop songs with an Irish singer as Gaeilge. They had some sort of bodhrán drum machine and clearly trad melodies.

Marc Fernandez told RTÉ:

I grew up in a fisherman's village in the south of Catalunya called La Ametlla de Mar, after that I moved to Barcelona. I studied Irish history when I moved to Ireland eight years ago and fell in love with it. I grew up speaking Catalan to one side of my family and Spanish to the other. I really believe in the importance of language to maintain cultural identity.

The journey out will shape the journey home.

stay at home here in Ireland and I'll never see you dispersed.

"I started to shoot the video for ‘Of The Sorrows’ on Christmas Day. I traded a couple hundred hours, a broken hard drive (had to start again), my sense of patience, and a broken leg I got on the last day of filming. But I could make peace with that deal. It felt good to give so much life to a project about a dying city."

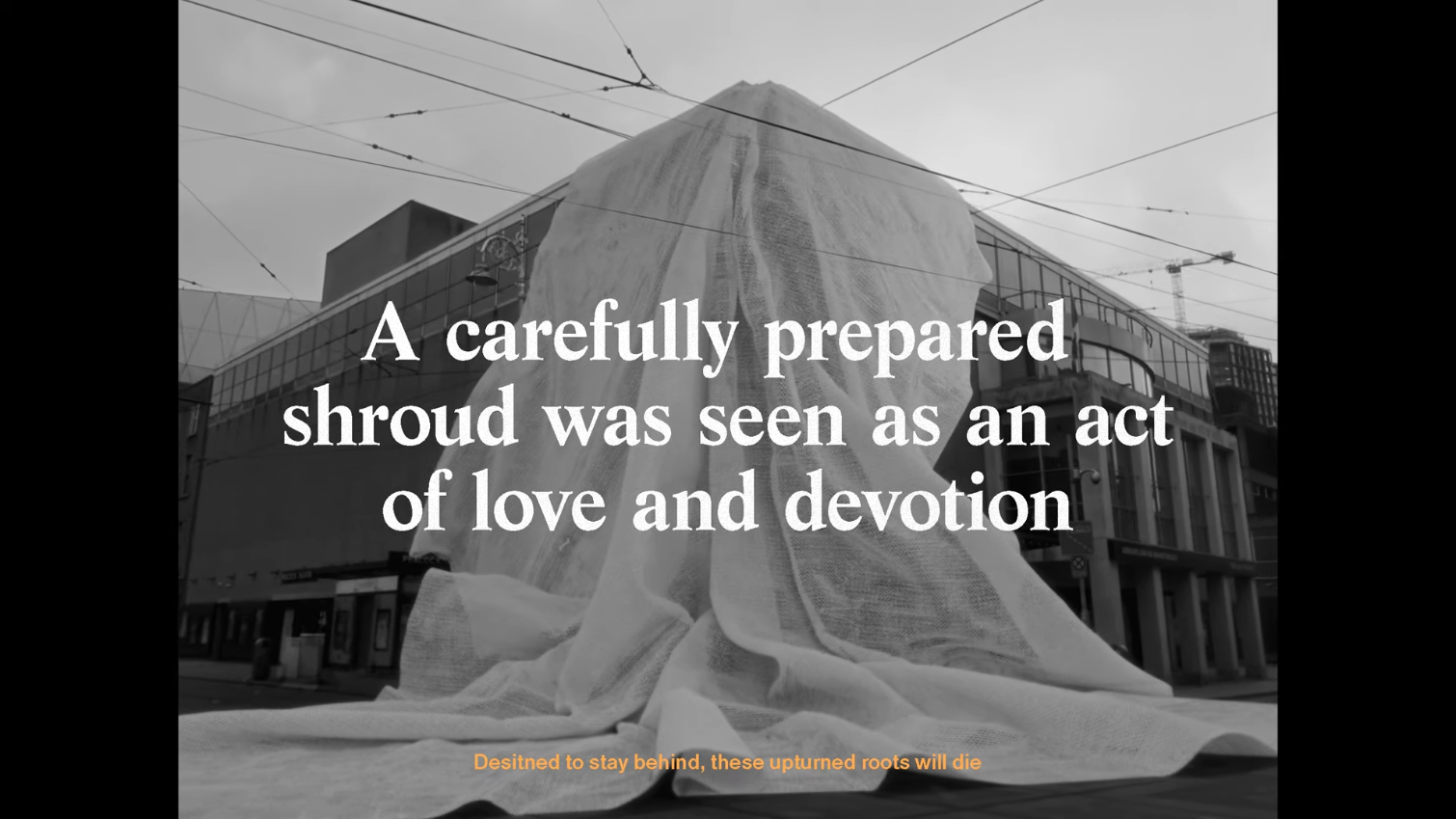

In his first new music release since the reissue of his debut album (and maybe going as back as far as Into a World... in 2020, depending on how you count it), Dave Balfe too keens for a dead town in his own language. The visuals of For Those I Love have been almost as crucial to the project as the music itself, as Balfe directs and does the VFX for most of his own videos. While the first record was a powerful expression of grief, Of The Sorrows introduces the symbol of the burial shroud, draped over Dublin landmarks piece by piece.

Of The Sorrows is well in the lead of the song-of-the-year stakes. It came out after I started writing this piece and yet it it's the exact confluence of so many of these ideas - the symbolism of death and burial, the idea of the dead town, mutating Irish tradition as an act of protest, rage against the fascists and the capitalists who left them the space to thrive, the hollowness left by the Celtic Tiger and the desire for something new to bloom in its absence.

The track begins as a slow crawl as Balfe spells out the cursed dichotomy between a Dublin that rejects him and a love of place, before an explosive verse slamming the far right ("some Landian scholar pent up on piss, shit, and squalor, spouting ouroboros horrors on the barstool") gives way to a rush of fiddle (played by Cathal Caulfield) and the track's final bargain:

There’s no peace across the sea for me

No world where I feel free

This building site that’s city wide

Is scattered with debris.

The only place that I can breathe is

With the bonnie rowan trees

I’ll never leave.

I have to leave.

I'll never leave.

I have to leave.

I have to leave.

And then, a found recording from somewhere: “I had to leave it but I want to die in it.”

I've been trading my "Sláinte"s lately for "bás in Éirinn" - a wish not for health, but "Death in Ireland" - that like Odysseus or perhaps Lullahush we will find our way home in the end. The toast is I picked up from my girlfriend's dad, but it's of course much older. For hundreds of years now, Balfe's dichotomy has been at the centre of the Irish identity - all we want is an Ireland worth living and dying in.

In Of The Sorrows, Balfe notes:

Stay here in Ireland

And you learn to bite your tongue

Because your labour puts the boot

Down on someone

No peaceful way to make a tonne

Like Kelly Earley's hypothesis that a normal life lived in Ireland is now an aspiration, many days I live in Dublin I wonder if my presence is making the place worse, if as someone who's come to call the city my home as an outsider I'm being brought in on a horrible gentrifying wind.

"Bás in Éirinn" is a wish not just for friends to return. It's a wish for an Ireland we can be proud to live in for the first place.

Or from the other angle, Brownsauce teamed up with Boyfrens to put out a free-download banger on Soundcloud in the first place simply titled "Fuk Dublin".

"Do you think they'd let me die the way I want to die if they're making it this hard to live?"

Or more simply yet again: "Respectfully, fuck Dublin."

The longer I live there, the more it becomes clear; if we're lucky enough to stay we have to fight for it still.